Eugenij ZAMJATIN

Eugenij ZAMJATIN

Eugenij ZAMJATIN

(Libedjan, Lipeck1884 – Parigi 1938)

ZAMJATIN, autore di fantascienza, è celebre per il suo romanzo distopico Noi (We)

IN QUESTA PAGINA: Introduzione – Biografia – Lettera a Stalin – La Pulce (commedia tratta da Il Mancino di Nikolaj S. Leskov) – la novella Noi (We)

Who Was Zamjatin?

Zamjatin was a Russian writer. He lived from 1884 to 1938, during the upheaval at the beginning of the Soviet Union. While his work is not well known since he was unable to publish most of it due to the censorship in Russia at the time, he was a very influential writer. Firstly he was a leador of the literary resistance under Stalin and inspired a lot of other writers. Secondly he was the father of modern distopia and his novel WE inspired Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s BRAVE NEW WORLD and they the later modern distopias

Zamjatin was a Russian writer. He lived from 1884 to 1938, during the upheaval at the beginning of the Soviet Union. While his work is not well known since he was unable to publish most of it due to the censorship in Russia at the time, he was a very influential writer. Firstly he was a leador of the literary resistance under Stalin and inspired a lot of other writers. Secondly he was the father of modern distopia and his novel WE inspired Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s BRAVE NEW WORLD and they the later modern distopias

Zamjatin: A Brief Biography

He was born in the province of Lebedyan in 1884 and was raised on the works of the great Russian romantics including Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Pushkin and others. He grew up under the rule of the last Russian Tsar, and in reaction against the opression and more importantly censorship of Tsarist rule, he became an active bolshevik revolutionary. When the revolution came, however, it brought no end to the censorship, and so he became a leader of the literary resistance. After repeated clashes with the government he reached the point that he was completely unable to publish anything. He went into volutnary exile in 1932 and lived in Paris until his death in 1937.

Zamjatin: A Brief Description of His Work

His works have beautifully crafted and poetic prose, rich in the styles of Russian folk-tales. He wrote many short stories as well as plays and novels. He was adept at using satire, sarcasm and irony to create vivid and poiniant tableaus of Russian life. Although Zamyatin’s works are almost completely unknown due to the censorship he suffered he remains a very important and influential writer.

Eugenij ZAMJATIN

Zamjatin was typical of many young men and women at the turn of the century in Russia. He despised the tsarist regime and wanted to work for radical social and political change. The fact that his father was an Orthodox priest probably intensified Zamjatin’s rebellious spirit because the Orthodox Church had long since joined forces with the tsarist government and supported its conservative, often repressive policies.

Zamjatin was typical of many young men and women at the turn of the century in Russia. He despised the tsarist regime and wanted to work for radical social and political change. The fact that his father was an Orthodox priest probably intensified Zamjatin’s rebellious spirit because the Orthodox Church had long since joined forces with the tsarist government and supported its conservative, often repressive policies.

Born in a small town (Lebedyan) in a provincial backwater southeast of Moscow, Zamjatin showed early ability at school and was admitted to the St. Petersburg Polytechnical Institute to study engineering. His political activities (joining the Bolshevik Party) got him arrested and exiled in the revolutionary year of 1905. Revealing the inefficiency of the tsarist police, young Zamjatin soon escaped from exile and returned to complete his degree. He graduated as a naval engineer in 1908 and even became a member of the Institute faculty, using his free time to write and publish stories about the colorful life of his hometown.

Only in 1911 did the tsarist police identify Zamjatin as an escapee from justice; he was arrested and exiled once again. Luckily for him, the tsar Nicholas II decided on a general amnesty in 1913 to mark the tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty. Thus Zamjatin again returned to St. Petersburg, legally this time.

RussiaIn World War I Zamyjatin was sent to Britain to work with local engineers who were building icebreakers for their Russian allies. But he continued to write, this time stories satirizing English conformism. He also learned more about the science fiction of H.G. Wells. Both the reluctance of English people to think for themselves (as Zamjatin saw it) and Wells’ stories played some part in the Russian writer’s most famous single work, the anti-utopian novel We, which he wrote in 1920-21 [see below].

After the collapse of the Romanov dynasty in 1917, Zamjatin returned to Russia. When Lenin and the Bolsheviks seized power in November that year, he already had grave doubts about the increasing gap between Bolshevik actions and their declared revolutionary ideals. But, as one of the few writers with an established reputation to stay in the new Soviet Union, he decided to do his best to support young writers. He helped inspire the creation of the “Serapion Brotherhood,” a group of talented writers who hoped to retain artistic independence under the new regime by declaring that they wished to keep politics out of art (the group took its name from Serapion, a hermit in one of the fictional tales by the popular German writer E.T.A. Hoffmann).

Through most of the 1920s Zamjatin was able to write and publish without much political interference. Too involved in a power struggle after Lenin suffered a stroke in 1922 and finally died in early 1924, Bolsheviks could not agree to a single party line on literature and the arts.

Zamjatin’s 1922 story “The Cave” about the cold and hunger suffered by people in Petrograd (as St. Petersburg was called at that time) offers an excellent illustration of his skill in using objects as symbols to reinforce the power of his portrayals. The cave of the story’s title is actually an apartment in which a cultivated couple belonging to the pre-revolutionary era burn all their precious belongings and sacrifice their cherished moral values in a vain effort to stay warm and survive. Thus the couple resemble Stone Age inhabitants struggling to avoid starvation in a windswept frozen landscape.

RussiaWith the triumph of Stalin in 1928, Party officials and their supporters became increasingly belligerent. All writers and artists were whipped into shape; those who protested or were recalcitrant (like Zamjatin himself) became targets to be vilified in the press. In 1929 Party hacks pounced on the fact that his novel We (never published in the Soviet Union) had appeared abroad in English and in other translations, to declare that Zamjatin was “counter-revolutionary”–this had already become a general term of abuse.

In those early days of the Stalinist era, the accused writer was able to respond in the press and to defend himself vigorously against the charges, but the public pressure continued. Although several other writers, including young men he had personally befriended and helped, joined the ranks of his accusers, Zamjatin refused to admit his guilt (this came to be called “recanting”). He had, however, become an “unperson” robbed of the chance to publish and thus earn a living. The authorities ordered his books removed from the shelves of bookshops and libraries.

Finally, in 1931 Zamjatin wrote a letter to Stalin declaring that he could no longer function as a writer in the Soviet Union and requesting permission to leave the country. Much to the surprise of many people, including perhaps Zamjatin himself, this request was granted.

Zamjatin went to live in Paris, which had a large Russian émigré population. They were mostly members of the old bourgeoisie or tsarist government officials, with whom he had nothing in common. He continued writing, but kept to himself until he died in 1937. His novel We remained on the Soviet black list for fifty years; it was finally published in a Moscow journal in 1987 during Gorbachev’s glasnost campaign

Zamjatin’s “Letter to Stalin”

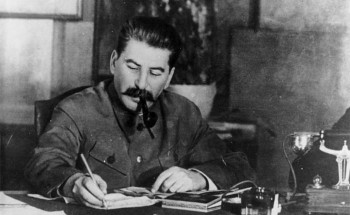

Stalin

In 1931, after a long campaign against him by the Soviet cultural establishment, Zamiatin has decided to make a desperate move and request a foreign passport by turning to Stalin himself (perhaps, encouraged by Maxim Gorky). surprisingly, permission was granted, and Zamiatin soon departed for the West as a Soviet citizen on an extended tour. Although Zamiatin never returned to Russia, his activities in the West suggest that he was careful not to burn his bridges. The letter below paints a vivid picture of the literary politics in Russia at the outset of the Stalin revolution.

June, 1931

Dear Iosif Vissarionovich,

zamjatin soviet3The author of the present letter, condemned to the highest penalty, appeals to you with the request for the substitution of this penalty by another. My name is probably known to you. To me as a writer, being deprived of the opportunity to write is nothing less than a death sentence. Yet the situation that has come about is such that I cannot continue my work, because no creative activity is possible in an atmosphere of systematic persecution that increases in intensity from year to year.

I have no intention of presenting myself as a picture of injured innocence. I know that among the works I wrote during the first three or four years after the revolution there were some that might provide a pretext for attacks. I know that I have a highly inconvenient habit of speaking what I consider to be the truth rather than saying what may be expedient at the moment.

I have no intention of presenting myself as a picture of injured innocence. I know that among the works I wrote during the first three or four years after the revolution there were some that might provide a pretext for attacks. I know that I have a highly inconvenient habit of speaking what I consider to be the truth rather than saying what may be expedient at the moment.

Specifically, I have never concealed my attitude toward literary servility, fawning, and chameleon changes of color: I have felt and I still feel that this is equally de grading both to the writer and to the revolution. I raised this problem in one of my articles (published in the journal Dom Iskusstv, No. 1, 1920) in a form that many people found to be sharp and offensive, and this served as a signal at the time for the launching of a newspaper and magazine campaign against me.

This campaign has continued, on different pretexts, to this day, and it has finally resulted in a situation that I would de scribe as a sort of fetishism. Just as the Christians had created the devil as a convenient personification of all evil, so the critics have transformed me into the devil of Soviet literature.

Spitting at the devil is regarded as a good deed, and everyone spat to the best of his ability. In each of my published works, these critics have inevitably discovered some diabolical intent. In order to seek it out, they have even gone to the length of in vesting me with prophetic gifts: thus, in one of my tales (“God), published in the journal Letopis in 1916, one critic has managed to find… “a travesty of the revolution in connection with the transition to the NEP” [New Economic Policy]; in the story “The Healing of the Novice Erasmus,” written in 1920, another critic (Mashbits-Verov) has discerned “a parable about leaders who had grown wise after the NEP.” Regardless of the content of the given work, the very fact of my signature has become a sufficient reason for declaring the work criminal.

Last March the Leningrad Oblit [Regional Literary Office] took steps to eliminate any remaining doubts of this. I had edited Sheridan’s comedy The School for Scandal and written an article about his life and work for the Academy Publishing House. Needless to say, there was nothing of a scandalous nature that I said or could have said in this article. Nevertheless, the Oblit not only banned the article, but even forbade the publisher to mention my name as editor of the translation. It was only after I complained to Moscow, and after the Glavlit [Chief Literary Office] had evidently suggested that such naively open actions are, after all, inadmissible, that permission was granted to publish the article and even my criminal name.

I have cited this fact because it shows the attitude toward me in a completely exposed, so to speak, chemically pure form. Of a long array of similar facts, I shall mention only one more, involving, not a chance article, but a full-length play that I have worked on for almost three years. I felt confident that this play, the tragedy Attila would finally silence those who were intent on turning me into some sort of an obscure artist. I seemed to have every reason for such confidence. My play had been read at a meeting of the Artistic Council of the Leningrad Bolshoi Dramatic Theatre.

Among those present at this meeting were representatives of eighteen Leningrad factories. Here are excerpts from their comments (taken from the minutes of the meeting of May 1~, 1928). The representative of the Volodarsky Plant said: This is a play by a contemporary author, treating the subject of the class struggle in ancient times, analogous to that of our own era… Ideologically, the play is quite acceptable… It creates a strong impression and eliminates the reproach that contemporary playwrights do not produce good plays… The representative of the Lenin Factory noted the revolutionary character of the play and said that “in its artistic level, the play reminds us of Shakespeare’s works…. It is tragic, full of action, and will capture the viewer’s attention.” The representative of the Hydro-Mechanical Plant found “every moment in the play strong and absorbing,” and recommended its opening on the theater’s anniversary.

Let us say that the comrade workers overdid it in regard to Shakespeare. Nevertheless, Maxim Gorky has written that he considers the play “highly valuable both in a literary and social sense,” and that “its heroic tone and heroic plot are most useful for our time.” The play was accepted for production by the theater; it was passed by the Glavrepertkom [Chief Repertory Committee]; and after that… Was it shown to the audience of workers who had rated it so highly? No. After that the play, already half-rehearsed by the theater, already announced in posters, was banned at the insistence of the Leningrad Oblit.

The death of my tragedy Attila was a genuine tragedy to me. It made entirely clear to me the futility of any attempt to alter my situation, especially in view of the well-known affair involving my novel We and Pilnyak’s Mahogany, which followed soon after. Of course, any falsification is permissible in fighting the devil. And so, the novel, written nine years earlier, in 1920, was set side by side with Mahogany and treated as my latest, newest work.

The manhunt organized at the time was unprecedented in Soviet literature and even drew notice in the foreign press. Everything possible was done to close to me all avenues for further work. I became an object of fear to my former friends, publishing houses and theaters. My books were banned from the libraries. My play (The Flea), presented with invariable success by the Second Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre for four seasons, was withdrawn from the repertory. The publication of my collected works by the Federation Publishing House was halted. Every publishing house which attempted to issue my works was immediately placed under fire; this happened to Federatsia [“Federation”], Zemlia i Fabrika [“Land and Factory”], and particularly to the Publishing House of Leningrad Writers. This latter took the risk of retaining me on its editorial board for another year and ventured to make use of my literary experience by entrusting me with the stylistic editing of works by y young writers including Communists. Last spring the Leningrad branch of the RAPP [Association of Proletarian Writers] succeeded in forcing me out of the board and putting an end to this work. The Literary Gazette triumphantly announced this accomplishment, adding quite unequivocally: “. . . the publishing house must be preserved, but not for the Zamiatins.”

The last door to the reader was closed to Zamiatin. The writer’s death sentence was pronounced and published. In the Soviet Criminal Code the penalty second to death is deportation of the criminal from the country. If I am in truth a criminal deserving punishment, I nevertheless do not think that I merit so grave a penalty as literary death. I therefore ask that this sentence be changed to deportation from the USSR and that my wife be allowed to accompany me.

But if I am not a criminal, I beg to be permitted to go abroad with my wife temporarily, for at least one year, with the right to return as soon as it becomes possible in our country to serve great ideas in literature without cringing before little men, as soon as there is at least a partial change in the prevailing view concerning the role of the literary artist. And I am confident that this time is near, for the creation of the material base will inevitably be followed by the need to build the superstructure, an art and a literature truly worthy of the revolution.

I know that life abroad will be extremely difficult for me, as I cannot become a part of the reactionary camp there; this is sufficiently attested by my past (membership in the Russian Social Democratic Party [Bolshevik in Tsarist days, imprisonment, two deportations, trial in wartime for an anti-militarist novella).

I know that while I have been proclaimed a Right winger here because of my habit of writing according to my conscience rather than according to command, I shall sooner or later probably be declared a Bolshevik for the same reason abroad.

But even under the most difficult conditions there, I shall not be condemned to silence; I shall be able to write and to publish, even, if need be, in a language other than Russian. If circumstances should make it impossible (temporarily, I hope) for me to be a Russian writer, perhaps I shall be able, like the Pole Joseph Conrad, to become for a time an English writer, especially since I have already written about England in Russian (the satirical story “The Islanders” and others), and since it is not much more difficult for me to write in English than it is in Russian.

Ilya Ehrenburg, while remaining a Soviet writer, has long been working chiefly for European literature for translation into foreign languages. Why, then, should I not be permitted to do what Ehrenburg has been permitted to do? And here I may mention yet another name that of Boris Pilnyak. He has shared the role of devil with me in full measure; he has been the major target of the critics; yet he has been allowed to go abroad to take a rest from this persecution. Why should I not be granted what has been granted to Pilnyak?

I might have tried to motivate my request for permission to go abroad by other reasons as well more usual, though equally valid. To free myself of an old chronic illness (colitis), I have to go abroad for a cure; my personal presence is needed abroad to help stage two of my plays, translated into English and Italian (The Flea and The Society of Honorary Bell Ringers, already produced in Soviet theaters); moreover, the planned production of these plays will make it possible for me not to burden the People’s Commissariat of Finances with the request for foreign exchange.

All these motives exist. But I do not wish to conceal that the basic reason for my request for permission to go abroad with my wife is my hopeless position here as a writer, the death sentence that has been pronounced upon me as a writer here at home. The extraordinary consideration which you have given other writers who appealed to you leads me to hope that my request will also be granted.

ZAMJATIN: La Pulce

(Sezione in preparazione)

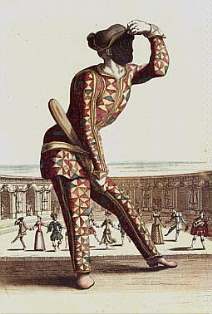

A motivi di fantasia popola>’e, COlI? e quelli -tsiti ne La vita dell’uomo di Andr‚ev, attinse Evg‚nij Iv…novi‚ Zamj…tin nel “giuoco -t quattro atti” La pulce, il cui “intrigo” era tratto da un racconto dello scrittore Tesk•v ~ mancino. Con questo “giuoco ” o commedia, ci sembra di tornare alle figure de Lo zar Massimiliano, mutato tuttavia il tono da tragico in scherzoso, sebbene sempre con la possibilit… di ricondul7e sia le une che le altre a quelle vive nel “balag…n” o ” baracca dei saltimbanchi ” della vecchia tradizione russa popolare. rur pubblicata nel I 92~ e messa in scena una prima volta al 2 ” l’catro d’arte ” e, in un testo un po’ modificato dopo la prima esperienza, di nuovo nel I 927 con la regia del famoso AT.F. Mon…chov e le scene del pittore li. 4!. Kust•diev al ” Grande teatro drammatico ” (gi… ifich…jlovskij) di Leningrado, La pulce, come dcl resto tutta l’opera di Zamj…tin, apparteneva a itt’atmosfera che be>t presto si vide quanto fosse estranea al reginte nato dalla rivoluzione: i~atmosfera che rese possibile la formazione del gruppo detto dci ” Fratelli di &~erapione ‘,di cui Zamj…tin fu appunto ispiratore e guida. Non meno chenella sua arte narrativa, eclettico di gusto e di cultura, anche nel teatro, Zamj…tin, che aveva maturato il proprio comunismo la vorando come ingegnere navale in Inghilterra e al n’torno in Russia, si era sentito subito sconvolto nelle idee e nella vita, iton aveva saputo nnunziare al proprio atteggiamento di critico della societ… capitalistica. Dopo un primo tentativo di dramma storico su Filippo Il, I fuochi di S. Domenico, ehefupub-

blicato a Berlino nel ~ 922, Zamj…tin aveva ridotto per le scene, col titolo La societ… degli onorevoli campanari, il romanzo Gli isolani, una feroce satira del mondo angio-sassone rivelatrice parc, dei turbamenti spirituali dello scrittore, il quale li concret• poi nel romatzo Noi proibito nella Russia sovietica, per poi dissintuiarli dietro la scherzosa, ma in fondo anche commovente, deformazione dei rapporti tra l’elementare mondo degli operai di l’ula che, per superare quelli inglesi i quali hanno,grazie alla perfezione della loro tecnica, costruita a grandezza naturale una pulce che balia, mettono alla pulce stessa gli stivali, fabbricati dalle loro magiche mani. Esperimento di impiego delle forme della commedia popolare russa¯, chiam• lo stesso Zamj…tin la sua commedia, aggiungendo che materiale tematico per la sua costruzione erano stati il racconto orale popolare sugli artigiani di Tula e, come abbiamo gi… detto, il racconto di Lesk•v, che dell’idea popolare era stato la prima elaborazione letteraria. cc Come la maggior parte degli autentici modelli di commedia popolare – aggiungeva ancora lo scrittore – ta ~lce non Š una commedia in senso stretto, ma piuttosto l’unione dell’elemento comico con quello drammatico, con prevalenza del primo cc. cc Mi Š sembrato oltremodo opportuno chiamare perci• La pulce “giuoco”: il vero teatro popolare non Š naturalmente un teatro realistico, ma un teatro convenzionale dal principio alla fine, che d… spazio alla fantasia e giustifica miracoli, improvvisi mutamenti, anaeronismi, quegli anacronismi attraverso i quali nel soggetto del giuoco ” (preso dai tempi zaristi) molto comodamente pu entrare anche l’attualit…Osservazioni che ci mostrano quanto viva dovesse apparire la commedia quando fu presentata al pubblico russo. Ricorderemo, anche a giustificare la nostra idea che proprio con La pulce si concluda un intero ciclo, che lo stesso Zamj…tin, segnalando l’impiego da lui fatto delle figure dei ” caldei ” presi carica turalmente dalle antiche ” azioni teatrali religiose “, paragonava queste figure a quelle della “commedia dell’arte ” italiana, a un Brighella, a un rantalone, a un P ulcinella, a immagine dei quali i ” caldei ” nel corso dell’azione cambiano varie volte la maschera, in una vera e propria molteplicit… e variet… di ruoli, compreso quello, cosi tipicamente popolare, di coinvolgere gli spettatori nelle vicende stesse dello spettacolo.